June 2012

First, some background on sound:

Humans are primarily visually oriented; we’re pretty good at using our eyes to perceive the world around us and attempt to make sense of it. It’s our eyes that keep us from bumping into solid objects and we’ve developed our vision to the point that we rely on it more than any other physical sense. Which is great if you are a visual artist because you sort of expect a certain level of understanding and comprehension of color and contrast from your viewers. People tend to know the color red when they see it – unless they’re color blind, so maybe that’s not the best example…Okay, if you see a picture of a cat, and you’ve ever seen a cat before, you know it’s a picture of a cat.

Audio artists don’t really have the same luxury. Sound is kind of weird. What we hear as sound is the oscillation or vibration of pressure in the air (or any matter, for that matter). Our ears are ridiculously complex and fragile mechanisms that direct these vibrations into our heads and transforms them from mechanical to electrical energy that our brains convert into what we call ‘sound’. Most of this is done with little tubes filled with thousands of tiny hairs. I told you it was weird.

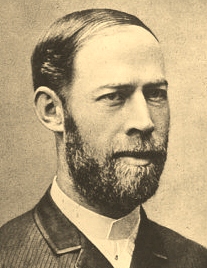

It is assumed that humans can perceive sound in the audio spectrum between 20 and 20,000 cycles per second (known in these parts as Hertz and abbreviated as Hz; and named after a guy named Heinrich Rudolph Hertz who apparently had nothing to do with automobile rentals) with 20 Hz representing earthquake-like lows (think Hip Hop bass) and 20,000 Hz sounding like a mosquito playing the highest note on the piano. As musicians, we manipulate and express these frequencies as ‘pitch’. We can perceive sound even lower than 20 Hz through our actual bodies, all the way down to about 4 hertz, but it is probably not a good idea to spend a lot of time in an environment like that. Dogs can hear up to about 60,000 Hz and that is why they can hear things like dog whistles and we can’t. Bats can perceive vibrations as high as 150,000 Hz! As we age, our hearing acuity diminishes quite a bit and we lose the ability to hear high frequencies very well. Most people only really hear up to about 10,000-16,000 Hz, and if you listen to the radio, the high frequencies are limited and chopped-off at 16,000 Hz (radio station transmitters encode other information in the super-high frequencies).

But what we generally do with our ears is hear people talk to us. Our speaking voices generate vibrations that are rich with multitudes of frequencies that form complex sounds which happen to be conveniently centered in the middle of our range of audio perception (approximately 60-7000 Hz). We call this middle area of the audio spectrum ‘midrange’ for fairly obvious reasons, and Humans have an amazing ability to discern extremely small variations in this range. This is one of the ways that we can tell the difference between one person’s speaking voice and another’s. We often refer to subtle changes in complex sounds as ‘tone’. I like to think of tone as the color musical artists use to ‘paint’ their musical pictures. When you like the sound of a singer you like their vocal colors and tones.

So, when a visual artist paints a picture of a cat, you probably will think, ‘Hey, there is a picture of a cat’. But when an audio artist plays middle C on the piano, unless you happen to have perfect pitch, you hear the pitch, tone, and duration of a sound that is simply floating in the air – waiting for the listener to endow the sound with meaning. You can produce more notes, connect them, and draw a musical picture, but unless you add words, it still has no intrinsic meaning that the listener can understand. The audio artist works in the vague world of soundscapes.

Still with me on all of this?

Let’s move to the world of practicalities.

My sweetie and I like to go to local music venues and hear live music whenever we can. I admit that I’m pretty neurotic about live sound. She knows about this particular nuance of my character quite well and every now and then will lean into my ear and whisper (or shout, depending on the show) “What’s wrong with the sound?” She used to suggest that I go fix it, but after becoming more aware of sound man protocols, she’s given that up. She’s told me that she used to think, before meeting me – that if the sound was bothering her it was because the music was bad. Think about that for a minute, my musician friends. Most people don’t know anything about what the person at the mixing board does, other than making the musicians louder. As far as they are concerned, the quality of the sound comes from the people on the stage, not the black-shirted person in the back of the room. The audience hears the singer say, “Hey can I have a little bit more of me in the wedge?” and the mysterious figure at the mixing board does something that has no apparent impact on what they hear. If a shrieking blast of feedback fries their Tympanic Membrane (ear drum), they’re gonna blame the people on stage. As a musician, you are held accountable for your sound, both live and in the studio.

When you are performing live, there are so many variables that affect the sound beyond your actual musicianship. The microphones, cables, mixing board, equalization, compression, monitors, main speakers, how many people are in the room, the temperature of the room, the shape of the room, what the room is constructed off, and where you are standing in the room – all can affect the quality of the sound that you’re audience is listening to. The person who is running the sound system has to take all of this into account and work with whatever equipment is available – to perform a function somewhere between the art of mixing and damage control. It’s not always a walk in the park.

The truth is that it’s not always possible to fix the sound. But there are things that musicians and sound engineers can do to minimize the problems. The biggest one is to reduce stage volume. I’m a guitarist; I like tube amps a lot and tube amps like to be turned up loud – they sound better that way. Turning them down puts a damper on the joy of playing music. Trumpets and drums don’t have volume controls, so I understand that turning down the stage volume is sometimes problematic. But it does help the sound engineer use the sound system to tame the room problems. It also can help keep the audience in the same room as you! I often suggest that guitarists and bassists use their amps as monitors and face them up at their heads rather than out into the audience, allowing the microphones and direct boxes to feed most of the sound at the room.

And your point is?

But my main point is that we can’t assume that most people understand the sound that they’re hearing because we use our ears mostly for verbal communication and most people are not trained to understand sound. They may enjoy it in a visceral way and ‘feel’ the music but they don’t know why it sounds ‘muddy’ or why they can’t hear the vocals. If your fans leave your gig talking asking each other ‘What was wrong with the sound?’ they’re likely to attribute the blame to the artist. So what can we do about it? As musicians and engineers, we can continue to educate ourselves in the audio arts, and we can be aware of not only performing music but to produce sound to the best of our ability.

I have many years of experience as a musician and an audio engineer but I freely admit that I am still learning and will continue to improve my skills in both endeavors. I will share my perceptions and revelations along the way with you all and encourage your interactions as well.

And whatever you do, don’t forget to bring earplugs…

dk

Will the cat be making future appearences in your blog? What would you use to mic up your cat?

In regards to the first question:

Possibly. She works for kibble.

In regards to the second question:

It really depends on context. As a diligent audio engineer, it’s important that I would ask you a few questions before making a recommendation.

Is it a solo cat or is it in an ensemble? Exactly what part of the cat are you planning on miking? Is it a live performance cat or are you planning on getting cat hair all over a recording studio? Are we talking about recording the next Josie and the Pussy Cats album, or are you going to record that sweet purr, pitch shift it down an octave, and create a demonic growl for your next blockbuster movie?

I once recorded a Cheetah’s purr on a Sennheiser MD421 and lived to tell about it.

dk